Context: We can study others who succeed, imitate their activities and gain their skills. But these activities create nothing new. Once we have reached their capabilities, how do we know if we’ve improved?

Completion metrics distract us from incremental improvement …

Creative efforts operate in an economy, a system where people manage limited resources to maximize return and growth. Economies drive everything. They need not involve currency. We can measure philanthropic efforts by the number of lives saved per unit of volunteer effort. We can measure companies by price-earnings ratio, market share, civic contributions, employee welfare, or religious conviction. We can measure artists by profit per work hour, the number of event attendees, the number of references on a social network, the devotion of fans, the artist’s technical improvement, the artist’s personal satisfaction, or the political effect of the artist’s message.

Forces

Economies

Different economies demand different behavior. Companies seeking profit may offer a variety of products for a single demographic, integrate a supply chain to reduce costs, or create viral marketing campaigns to exploit human curiosity. A company seeking civic return may invest in public art. A company promoting libertarianism may invest in anonymous currencies, such as Bitcoin.

Economic actors—individuals, teams or organizations—who operate without a well-defined economy wander aimlessly. They don’t know what they value: Are they pursuing revenue growth, customer growth, user engagement, brand recognition, saving lives, fewer security risks, higher employee retention or awards for good citizenship? They don’t know their costs: Are they managing staff availability, training time, marketing spend, executive meeting time, consultant time?

If bosses have no clear economy, employees develop their own. However, nothing keeps different employee economies aligned. Some will become sycophants bending to the boss’s apparent whims: one week they pursue one thing, and the next week something completely different. Some will collaborate, and others will compete (damaging collaborators and the organization). Some will pursue revenue by increasing marketing efforts, and others will pursue cost reduction by reducing marketing efforts. Whether individual, company or nation, economic actors without a compass will likely dither and fail as their unguided efforts cancel each other out.

Consistent economic focus can generate great outcomes. The Gates Foundation, for example, has invested in economies most philanthropies shun, such as malaria eradication and standardized education. Many first world wealthy donors don’t worry about malaria. They prefer charities that realize local benefit at low cost with low controversy: civic art, homeless shelters, local education. Malaria reduction costs a lot and generates first world controversies, such as pesticides, swamp draining and vaccination. The Gates Foundation’s resource limit appears to be time, not money (funded by Bill Gates and Warren Buffett) and not universal acceptance. Its speed, once it makes a decision, is breathtaking. Its goal is to “help people live healthier and more productive lives.” The Gates Foundation follows its goal inside its unique economy, experimenting with new approaches along the way. As a result, the Gates Foundation has rapidly become one of the world’s most admired charities.

Measurement

The most accurate measurements of success can significantly lag the completion of creative work. The works of many destitute artists, long dead, can command millions today. Many ultimately successful startups required years of investment before they turned a profit, often with few or no rewards for the founders. Therefore, obvious economic metrics, such as stock price or quarterly profit, serve poorly to measure the likelihood of success for current creative activity. Lagging metrics applied to current decisions can fail perversely. For example, creative effort to build a strong asset can cost money. If this cost is characterized as a current loss, the company may invest badly [Agile Capitalization].

Progress metrics (or “leading indicators”) provide short-term guidance. Creative economies are chaotic systems. We can use progress metrics to forecast short-term results, but predictions from any metrics in a chaotic system worsen exponentially with time, making long-term forecasting impossible. Better progress metrics may correlate better with long-term success, but perfection is a mirage. Chaos even changes the utility of progress metrics: those that work now may perform badly later.

We get what we don’t measure. —Troy Magennis

Progress metrics that are blind to significant risk, such as measuring untested and unreleased software production, often do not correlate well with desired outcomes, and thus produce bad decisions. This explains why agile methodologies advocate rapid and frequent releases to customers.

A single metric rarely serves to guide wise decisions. Many organizations measure value without cost, or visa-versa, but this usually produces inferior outcomes. For example, if we seek revenue growth alone, we can achieve this by spending more on marketing or cutting our prices below cost. If we seek greater production from teams, we can measure and reward velocity improvement, but this may encourage teams to work on better understood, lower value features.

Costly metrics inhibit frequent monitoring and produce inaccuracies. For example, detailed surveys with dozens of questions will be skewed towards respondents who have spare time, others will partially complete the survey or ignore it completely. Follow-up surveys will likely get even fewer responses. The one-question Net Promoter Score survey, used pervasively in customer service and product evaluations today, reduces this effect.

Managers demand forecasts to make decisions, and many such decisions cannot be deferred. They prefer to make decisions with “hard numbers” (unqualified commitments), but chaotic environments produce probability distributions. Managers rarely demand probabilistic forecasts, but as a result they make poor decisions.

Considering too many metrics creates confusion and misalignment. Not everything that can be counted counts (Cameron 1957). For example, the number of web site visits during a television ad campaign might correlate with brand recognition or not; we must test this assumption to avoid wasting money. Many organization measure and report everything thought to be interesting, all the way up to executives. But this increases cognitive load and decreases decision-making quality.

Many cognitive biases skew subjective measurements. They affect team estimates, customer surveys, employee performance assessments, and management scorecards and more. Anchor bias—the effect that the first estimate mentioned by a person attracts similar estimates from other people—is especially powerful in teams.

Every economy evolves: this year’s resource limits are next year’s surplus and visa versa. For example, startup companies initially need to show market traction, making revenue and growth more important than cost control. Later in their lifecycle, these companies need to show profitability. Ultimately, shareholders may demand a dividend.

Variation accompanies creativity and chaotic economies. Aggressive attempts to control variation can destroy creativity. The Six Sigma and ISO 9000 methodologies control variation and improve quality in manufacturing. Well-intentioned process gurus applying Six Sigma to product development destroyed innovation in several companies (Cagen 2009), including 3M (Huang 2013).

Rewards

Misapplied measurement can encourage dishonesty. Rewarding people who achieve metric goals, and especially punishing people for failing to meet metric goals, encourages gaming. In creative fields, metrics may involve judgment. Who will objectively tell us we have gotten a more enthusiastic audience reaction, better usability, higher velocity, or higher customer assessment?

For example, I have received “thank you” letters from auto mechanics saying, “You will receive a survey from the manufacturer asking for your feedback. We value an all-5 rating on our services, and ask you to call us if there are any problems.” This form of gaming exploits anchor bias, giving us a number we are likely to repeat. The most creative people seem to love to game metrics; it’s fun! But the culture of dishonesty that arises damages organizational productivity and innovation.

People can game perceived value by omitting measurements. For example, I once worked with a highly regarded marketing group. In weekly meetings, department heads would announce metric results. I gradually realized department heads always provided highly precise numbers when they were positive, and qualitative answers when they were negative. Half of the information was missing—the negative half. I decided to confront the group. “A little down in the year-over-year percentage,” announced one department head. I raised my hand, and described my observation. “So here we have an example of a negative result that is ‘a little down,’” I said, “What is the number exactly?” The department head said, “Um, it’s down 87%.” The room was silent. The department head looked embarrassed. I asked, “How come?” He said he wasn’t sure. He later shared with his peers that I must have been targeting him. Further investigation revealed that factors outside his control caused the decline. However, because he feared repercussions, he failed to share the data and no one had investigated the problem.

Monetary reward fails to produce better creativity. Daniel Pink popularized the discovery that creative people succeed when they are motivated by mastery, autonomy and purpose (Pink 2010). But when we offer money, they perform badly; when we offer more, they perform worse. This does not require us to discard economic metrics; it reveals that mastery, autonomy and purpose desire major elements in our economy.

… therefore, evolve leading indicators to fit the work

To measure progress, articulate what you truly value, find metrics to detect progress or retreat, and measure frequently. The best progress metrics for agile actors are low-cost (so you can run them frequently) and fast (so you can adapt rapidly). For example, simple Net Promoter Score surveys sent to a random sample of customers or employees can measure happiness or loyalty in a single question.

We use data to make decisions on everything.—John Campos, Facebook CIO

Identify desired outcomes

Identify the biggest economic actor you influence (e.g., the company if you are an executive), examine its economy and articulate its goals. A mission statement lists timeless objectives, a vision statement lists multi-year objectives, and goals are short-term objectives (a year or a quarter). Examine these objectives. Do they align? If not, work to reconcile them. Construct a concise, specific description of your current strategic activities at each time scale. Do they align with the objectives? Again, work to reconcile them. Gain consensus from colleagues that everyone will seek these outcomes. The better you can align desired outcomes, the more stable your metrics will be over time and the more productive your efforts. [Collective Responsibility]

You should acknowledge unstated values in your economic metrics to the extent you can, because then you can align employee work with achieving those goals. When values are left unstated, misaligned values generate office politics between those with a clue and the clueless.

Of course, as with all significant corporate transformations, diplomacy may be important. If an unstated corporate value is implementing the pet projects of the CEO’s spouse, you probably don’t want to write that down. If the projects have coherent goals, however, you may be able to simultaneously endear yourself to the CEO’s spouse and help align the efforts of the company by articulating those goals.

Identify relevant metrics

To identify progress metrics, consider the desired benefits of better measurements (Maccherone 2017):

- We seek better progress measurements because

- Better measurements lead to better insights

- Better insights lead to better decisions

- Better decisions lead to better outcomes

Our mission, vision and goals describe the outcomes we seek. We work backward from desired outcomes to determine the measurements we perform; hence this technique is called ODIM (outcome, decisions, insights, measurement). Starting from a desired outcome, look at key decisions that lead to it, insights that help you make those decisions, measurements that will generate insights. Now you have candidate metrics that will likely lead to better outcomes.

Evaluate and refine your metric suite. Here are some important criteria:

- Keep the number of metrics low. People cannot easily consider more than 7 concepts in making decisions [Chunk before Choosing] Hoshin Kanri, an executive practice at Toyota, argues for choosing a few “Careful KPIs.”

- Depending on the economy, we may have to make rapid decisions. Make sure metrics can be measured frequently without adverse organizational impact.

- Balance metrics against each other to reduce perversity. For example, include both revenue and cost metrics.

- Identify subjective metrics, and consider ways to reduce bias.

- Progress metrics forecast the near term future. Consider growth rates, variance and other derivative metrics that may improve decision making.

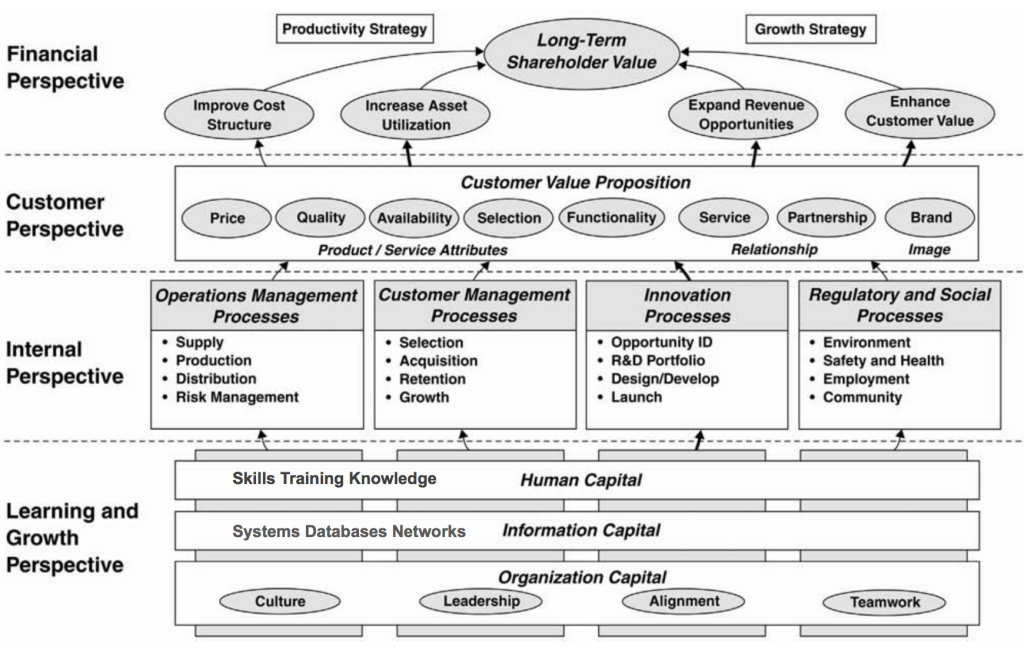

Align goals from top (executive) to bottom (individuals). This can be done effectively with Strategy Mapping (Kaplan & Norton 2004). Proceed top-down to create desired outcomes and measurements—start with the company’s perspective first, then derive the department, team and employee desired outcomes and measurements. This will harmonize and mutually reinforce everyone’s work. Gain the consent of executives to promulgate the economy, broadcast it through meetings and internal media, and work with lower-level actors to identify their narrower, but aligned, desired outcomes and measurements.

Consider whether the metrics omit an important class of value, cost, risk or elasticity. Can you improve the outcome by change the metric, the process step where it is sampled, or the process rules? Scrum, for example, insists that teams can release software at the end of every Sprint. This ensures that velocity incorporates testing, packaging, localization and other important activities, and thus makes velocity-based forecasts more accurate.

Create a forecasting discipline

Establish an approach for forecasts. Scrum includes a bias resistant forecasting technique for delivery time based on velocity, story point estimation and “planning poker”. However, it cannot responsibly model deferred risk. Monte Carlo simulation can improve forecasting results significantly (Magennis 2015).

Lazy statisticians often assume distributions are normal, to simplify conclusions. However the probability distribution for creative work completion is likely Weibull, which has a long, fat tail (Magennis 2015). Bad analysis arises from making assumptions about probability (Cagan 2009).

Never report forecasts without including probability (Maccherone 2017), especially when these forecasts are used for significant business decisions. For example, simple delivery forecasts from Scrum should be “50% likely to deliver by .” If decision makers demand more details, use more sophisticated modeling. Forecasts can be “simplified”, such as by omitting probability distributions, but this can lead to bad decisions. Forecasters must be alert and convey details where they have been omitted.

Embrace objectivity

Resist the temptation to reward personal creativity with money, as this will degrade metrics. Better motivators are mastery, autonomy and purpose. Even giant conservative oil companies have used these principles to guide performance management (Koch 2007).

Encourage objectivity and learn from both success and failure. When failure has no cost, the greatest learning occurs when we challenge ourselves to achieve a 50% failure rate (Reinertsen 2013). Reducing the cost of failure (such as by limiting work-in-process) can improve reporting. Be wary of “missing information” and encourage the organization to demand information from failures and successes alike. Executives can model the behavior they want by comfortably discussing their own failures, before asking employees to reveal theirs. They can reinforce this objectivity by rewarding employees who learn from failure, perhaps with greater autonomy.

Evolve

Commit to a regular cadence to review and evolve metrics to meet emerging needs. Metrics that serve well at the beginning of a long project may not work toward the end.

Metrics cannot replace thinking. Creative endeavors are not predictable manufacturing efforts. Therefore, don’t imagine that we can robotically transfer metrics to action. We must think about the consequences and their relationship to our desired outcome. If we divert from the desired outcome, we may need to consider changing the metrics.

Examples

Software project have a sordid history of outrageously expensive project failures (Charette 2005). Many of these failures arose due to failures to understand the production economies of software development, to measure progress well. Agile methodologies largely improve outcomes due to better progress metrics and forecasting that arise from short release cycles.

Some companies have incredibly generic (and useless) mission statements, such as American Standard Company’s mission to “Be the best in the eyes of our customers, employees and shareholders.” In this case, and even in companies with great mission statements, look deeper. What do the CEO, executives and the company value? I once worked for a company that supported pet adoption, veterans and Bitcoin. It also built a supply chain infrastructure that supported “mom and pop businesses.” I concluded that the company valued the underdog, and that we should add “helping underdogs” to the company’s mission. Some companies seek media exposure for their brands or executives. If so, that too should be in your declared economy.

| Outcomes |

|

| Decisions |

|

| Insights |

|

| Measurements |

|

We can use malaria eradication as an example of the ODIM (outcome, decisions, insights, measurements) approach to finding good metrics. See the table above.

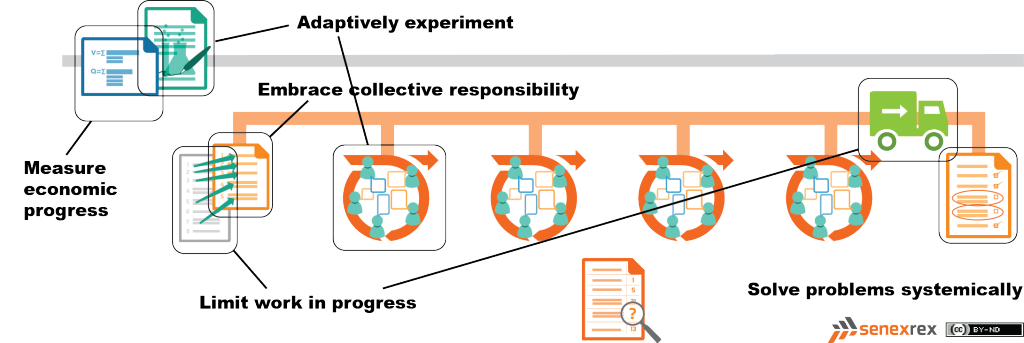

If you know the Scrum agile methodology, the figure above will be familiar. A short definition of Scrum is rhythmic experimentation to improve production. The upper-left meeting in the diagram is the Retrospective Meeting. This meeting is the most important in Scrum (sadly, most Scrum teams don’t do it). It has four steps:

- assemble and discuss progress metrics,

- brainstorm and identify process changes,

- hypothesize progress metric changes resulting from the new process

- commit to the new process rules for the next Sprint

Scrum retrospectives focus on production progress metrics, which are virtually all about cost. Velocity is a leading progress indicator correlated with feature delivery rate. Task progress is indicated by velocity alone, but Scrum’s double-loop learning goal is process improvement, and that metric is velocity improvement or acceleration. The Happiness Metric is a quick survey of team members indicating the average happiness of team members, and is correlated with better communication, trust, alignment and self-regulation, similarly we are looking for happiness to improve. Bug Fix Time is a measurement of the time from receiving a bug report from a user until it is fixed in the field, and, as with all progress metrics, we are looking for improvement.

Many commonly used agile patterns improve the accuracy or speed of progress metrics. The Story Point Estimation pattern helps disassociate estimated effort from actual effort, reducing optimism bias and creativity inhibition. The Relative Estimation pattern obtains statistically responsible acceleration metrics. The Delphi Method pattern reduces anchor bias and increases deep thinking by preventing people from basing their estimates on a respected peer’s estimate. The Fibonacci Estimation pattern limits estimates to Fibonacci numbers, such as 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, …, to avoid teams wasting time estimating to greater precision than accuracy warrants. All of these patterns are usually combined into a pattern called Planning Poker.

The Lean Startup agile methodology uses economic metrics tied to value rather than cost, such as customer engagement, bounce rate, click-through rate and Net Promoter Score. Lean Kanban uses economic metrics related to flow, such as work-in-progress, queue length, blocker count, lead time, cycle time and throughput. Toyota Production System uses economic metrics related to waste-reduction, such as defect count, lead time, knowledge production and rework. OODA uses economic metrics related to battle, such as reaction time and enemy disorientation. Getting Things Done has economic metrics related to focus, such as last review date, inbox size, and today’s to-do item count.

Failure analysis has been elevated to an art form by Engineers Without Borders Canada in its Admitting Failure web site (Good 2018). Here, civic organizations can submit case studies of failures. “Fear, embarrassment, and intolerance of failure drives our learning underground and hinders innovation. No more. Failure is strength. The most effective and innovative organizations are those that are willing to speak openly about their failures because the only truly “bad” failure is one that’s repeated.”

Resulting Context

In adopting this first agile base pattern, organizations and individuals obtain coherent mission, vision and goals. The organization will use a handful of evolving metrics to gauge progress. It will learn faster from both failure and success. It will more accurately forecast future events by incorporating probability distributions. In short, it will understand its economy and its achievements better.

Does the Measure Progress with Leading Indicators pattern ensure that we are agile—that we can rapidly sense, adapt and create to match a chaotic economy? No, that we merely measure progress doesn’t guarantee we will improve. However, when progress measures are visible, people naturally want to improve. If progress metrics are easy to perform, and if the corporate culture supports experimentation, agility may emerge. We don’t want to leave that to chance, however, so the remaining agile base patterns lock it in.

Aliases

- Careful KPIs (Hoshin Kanri)

Related Patterns

- Velocity, Happiness Metric, Rework Cost aka Bug Count (Scrum)

- Strategic Vision Alignment

- Backlog Prioritization (Scrum)

- Evolution vs Revolution (Hoshin Kanri)

- Definition of Done (Scrum)

References

Related Work

The five Agile Base Patterns are described in detail at Senex Rex. See Measure Progress with Leading Indicators, Proactively Experiment to Improve, Limit Work in Process, Embrace Collective Responsibility and Collaborate to Solve Systemic Problems. Subsequent posts will explore patterns beyond these basics. Subscribe below to be notified when new posts go live.

Acknowledgements

Scott Siegal provided a detailed review. Larry Maccerone and Troy Magennis invited me to their Agile Metrics course, which supplied many ideas in this pattern. All errors are mine.

Author

Dan Greening

Senex Rex tackles challenging problems at the agile management frontier. We help companies, teams and leaders accelerate and sustain value and quality production, so we can all live better lives. Contact us for help with agile transformation, turnaround management or performance improvement.